It’s no secret that our 100% cotton Lettra paper is coveted by letterpress printers. In fact, we like to say it goes together with the printing process like Fred and Ginger. But, we never thought of our Lettra as the perfect canvas, but luckily, artist and Vermont College of Fine Arts student Wendy Briggs Powell did.

“Six months ago, I had been dying strips of various papers on a smaller scale. I knew I wanted to work larger,” she recalled. “Another student has been using Lettra for her letterpress work and I went crazy over the feel and heft of her take-away cards at residency! So I thought Lettra was just the right paper to create larger pieces that would withstand soaking for many hours, days even, in containers of dye. I was right! And I do love the pairing of old and new as well.”

Below is a video as well as images of Powell’s Lettra canvas along with a little about her process.

“When making watermarks in my studio, I have found that each container, and the amount of water I fill it with, lends itself to different possibilities of mark-making. What I discover as I try to create compositions from these colored forms is that one vessel size and shape is good for making curves, another for straight lines and another for creating a line in the middle of a sheet.

For instance, I can create a wave-like motion within the container by gently (or not) rocking it. The waves leave their mark on the paper. The length of time the paper soaks determines how intense the color will be.”

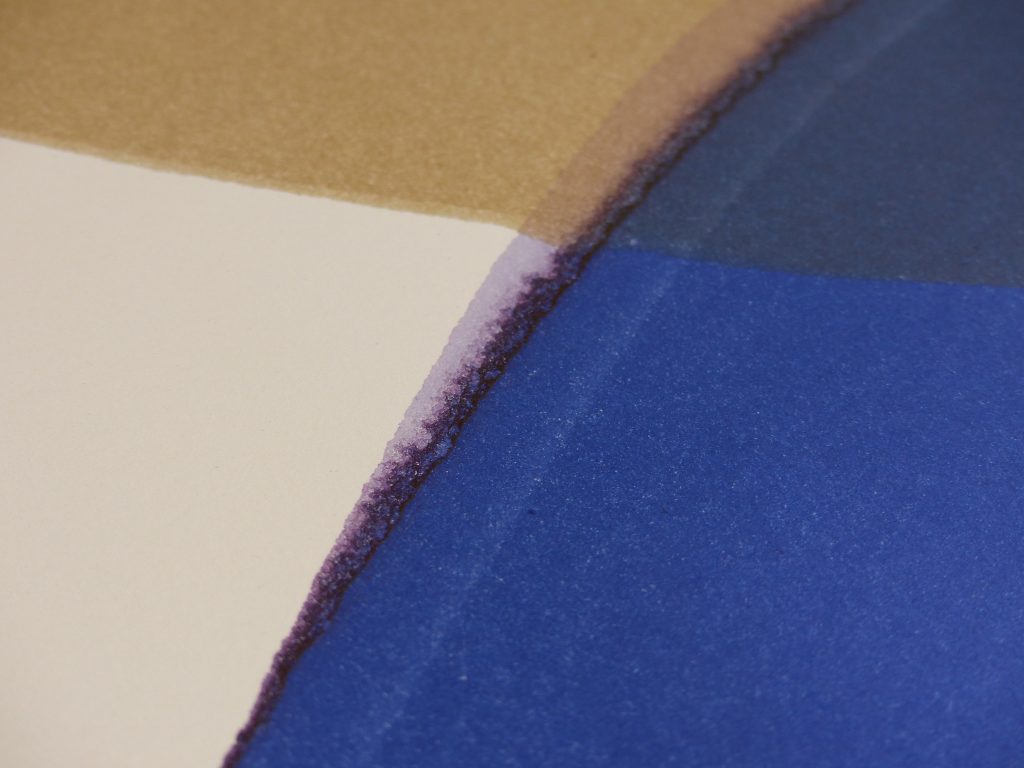

“By bending the paper, I can create curves and angles. Altering the way I position the paper, allows for organic shapes to emerge on their own. By soaking different parts of the paper in different colors, I can overlap and create new colors and shapes.

“By bending the paper, I can create curves and angles. Altering the way I position the paper, allows for organic shapes to emerge on their own. By soaking different parts of the paper in different colors, I can overlap and create new colors and shapes.

I am guiding both the water and the paper while respecting their inherent properties. I can’t direct the water to go exactly where I want it to go or make it follow the line I envision, I can only coax it into its natural place. The same is true for the paper. I can’t make the paper bend in all directions without creasing and I can’t make it absorb water more quickly than it is able. I work with the paper as it is, letting it reveal its intrinsic beauty to me.”

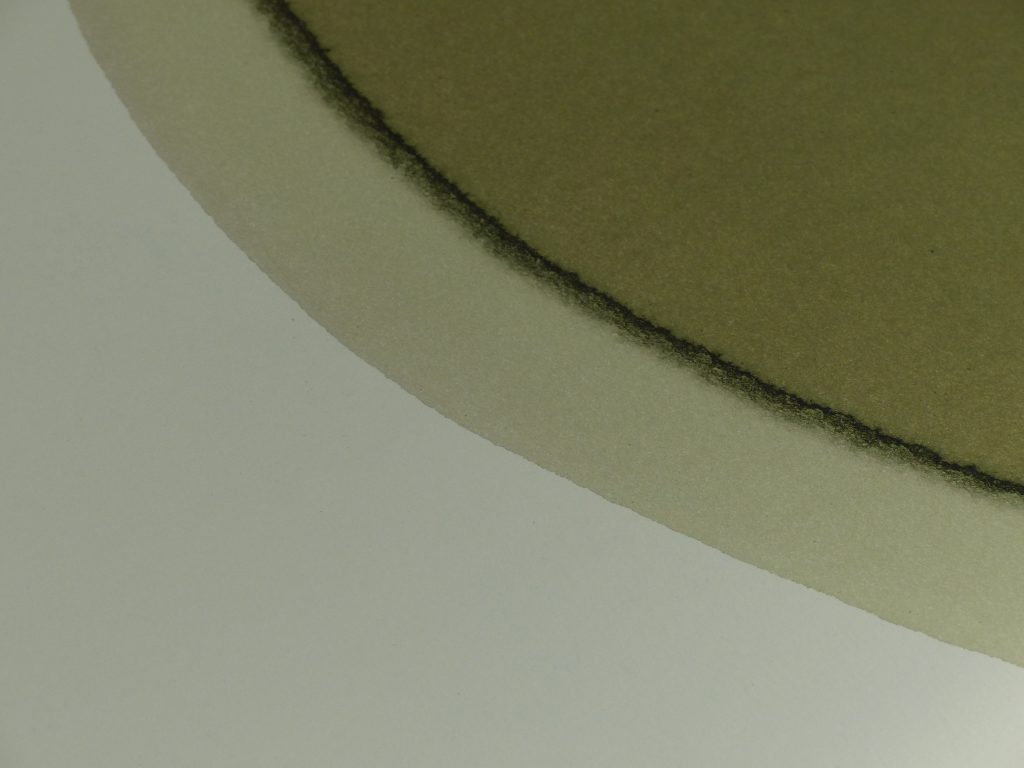

“Additionally, I discovered that by saturating the paper for many hours in one color without repositioning it, I can create a distinct sedimentary line at the edge of the shape the water has formed. This line contains more pigment than the rest of the shape. Therefore it makes a stronger edge to the shape itself. In a deep and narrow vessel, the line is more predictable given how the paper sits. In a shallower container, the paper moves over time and the lines become less predictable, reflecting the water’s slow movement. This line is interesting to me as a metaphoric threshold where water meets air on the paper. It also becomes another variable to try to work with.

“Additionally, I discovered that by saturating the paper for many hours in one color without repositioning it, I can create a distinct sedimentary line at the edge of the shape the water has formed. This line contains more pigment than the rest of the shape. Therefore it makes a stronger edge to the shape itself. In a deep and narrow vessel, the line is more predictable given how the paper sits. In a shallower container, the paper moves over time and the lines become less predictable, reflecting the water’s slow movement. This line is interesting to me as a metaphoric threshold where water meets air on the paper. It also becomes another variable to try to work with.

For instance, while working with the sedimentary lines, I often play with breaking a line with another color or allowing it to soften by repositioning the paper and allowing a wash of that same color to expand beyond that hard edge. This got me to thinking about my own boundaries and how I create my own hard lines. There are times when I need to strongly define my own edges and other times where I can soften.”

“For the most part, I can only create the conditions for this sedimentary line. In general, the line is subject to whatever the water does. It’s a practice in giving up control and working with the way things are. The same can be said about life.”

“For the most part, I can only create the conditions for this sedimentary line. In general, the line is subject to whatever the water does. It’s a practice in giving up control and working with the way things are. The same can be said about life.”